Aberrations in British Butterflies

Review by Melanie Penson

A brief historical context

British butterfly enthusiasts have been fascinated by aberrations or 'vars' (variations) probably before the founding of the Aurelian Society; the exact date of which is obscure but somewhere between 1720 and 1740. This was a Golden Age in lepidopteran discovery, before all known British native species had been discovered. A time when a keen naturalist could wander into their local wood and make original discoveries: a new species or aberration before lunch.

Caught up in the Zeitgeist, a kind of mania for butterfly aberrations swept through British entomologists and the amassing of vast private collections was not only socially acceptable but almost to be expected. The Aurelian Society provided a venue for enthusiasts, be they duke or dustman, to meet and converse on equal terms. It must be said that the former did more 'collecting' with their cheque books than they would ever do with their butterfly nets!

Sites where aberrations abounded were often jealously guarded; such as armed game keepers postes at the entrances to some of the New Forest inclosures; but on more open sites, such as Therfield Heath in Hertfordshire, it was more of a free-for-all. This site was famous for producing some extreme variants of the chalk-hill blue. It still occurs there but not in its former numbers and it is understood that the incidences of aberrations has also fallen.

So popular had the amassing of 'vars' become that a few unscrupulous dealers resorted to painting extra markings on otherwise ordinary butterflies, gave them a fake name and sold them at astronomical prices to an incredulous clientele, eager for novelty. Such fraud was possible because there were no guide books and the often verbose descriptions in the available literature was often inacessible to all but the wealthiest collectors. To make matters worse, equally eminent collectors, working and publishing independently, were giving different names to the same aberrations. No wonder confusion reigned.

Little attempt was made to classify the aberrations of our butterflies until comparatively late in the 19th Century and it was only with the founding of Ecological Genetics as a distinct science that some semblance of order was brought forth. E.B Ford's seminal publication Butterflies in the New Naturalist series in 1945 was the first book to examine the whys and wherefores of aberrations and examine the question: Genetics or Environmental Conditions?

Although Ford had a huge personal collection of aberrations (mostly marsh fritillaries, meadow browns and common blues: his most important objects of genetic study), his book was not a field guide and the few aberrations that are pictured serve to illustrate his scientific opinions.

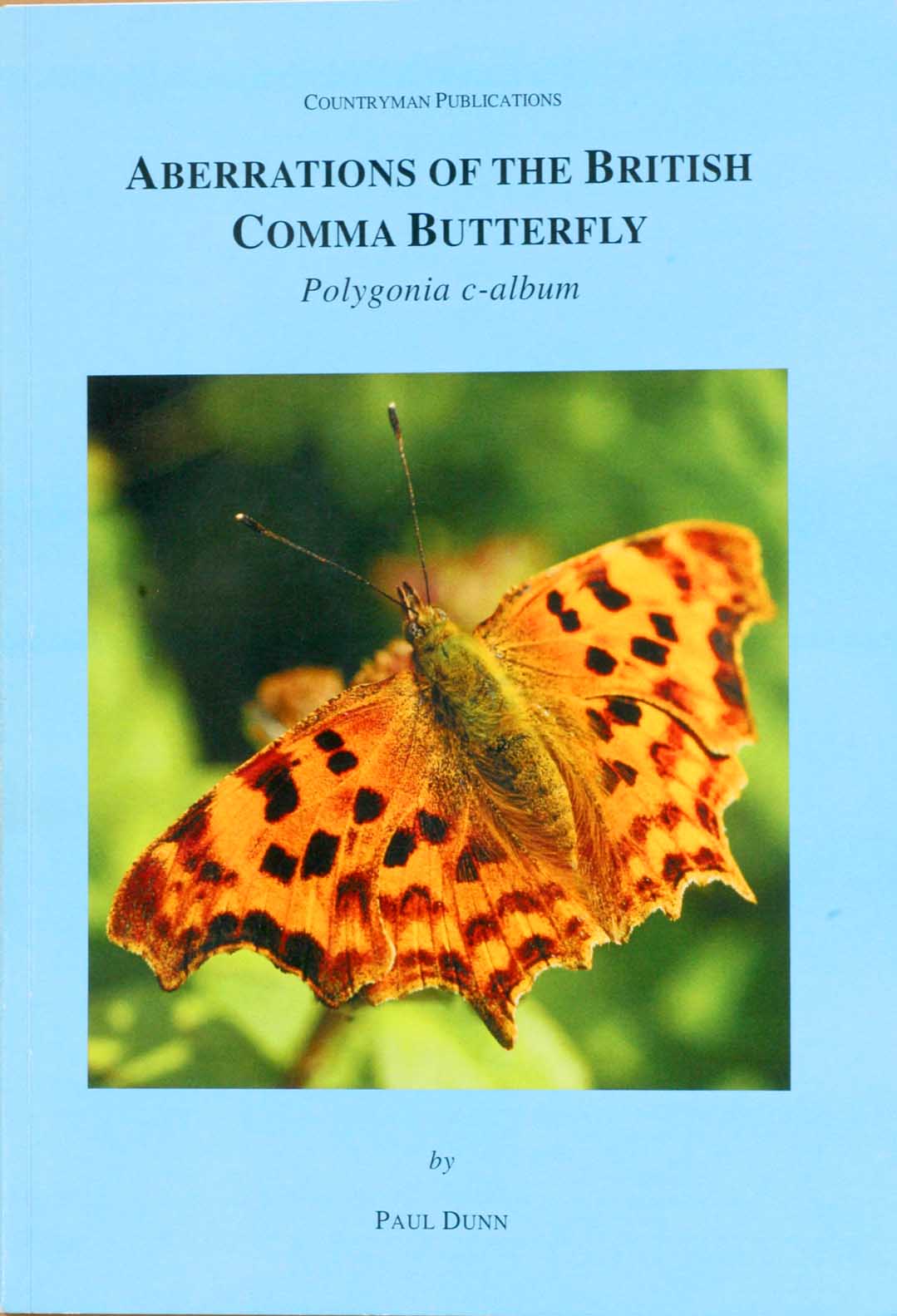

F.W Frowhawk published a book on aberrations in 1936. It wasn't until 1978 that Aberrations in British Butterflies by A.D.A Russwurm was published that provided 40 colour plates of paintings, featuring all British species. Even this publication was far from comprehensive and it only illustrated the more extreme aberrations; for example; 3 of the Comma and; 4 of the Ringlet (see review below).

Another book entitled Variations in British Butterflies appeared in 2000 by A.S. Harmer and illustrated by Russwurm. This book includes a few photographs as well as the paintings. Both books include lengthy chapters on genetics and how the aberrations have arisen. Both also cover the entire British butterfly fauna, which doesn't leave much room to cover the entire range of aberrations and again only the most striking examples are illustrated.

Step forward Paul Dunn.

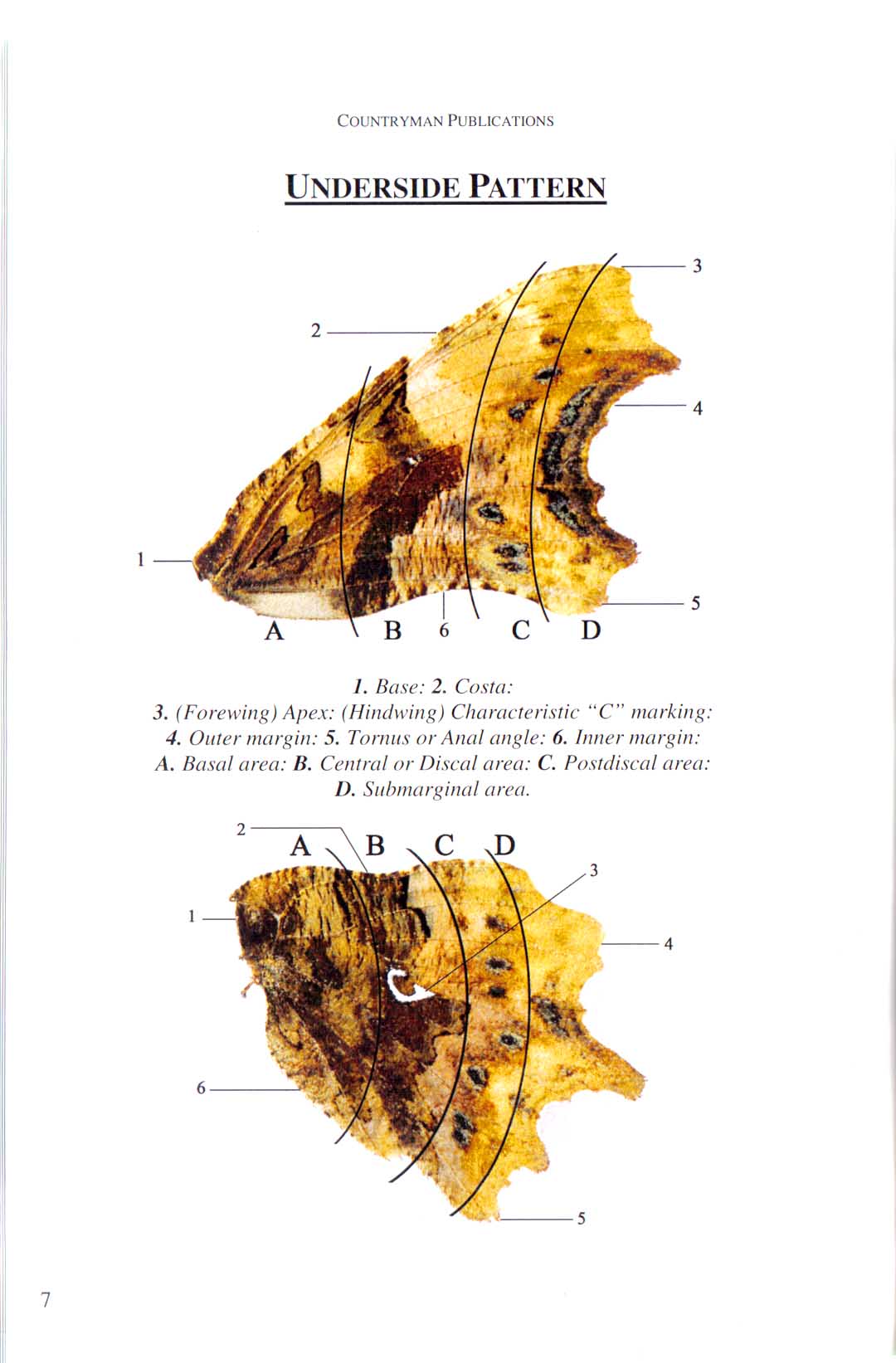

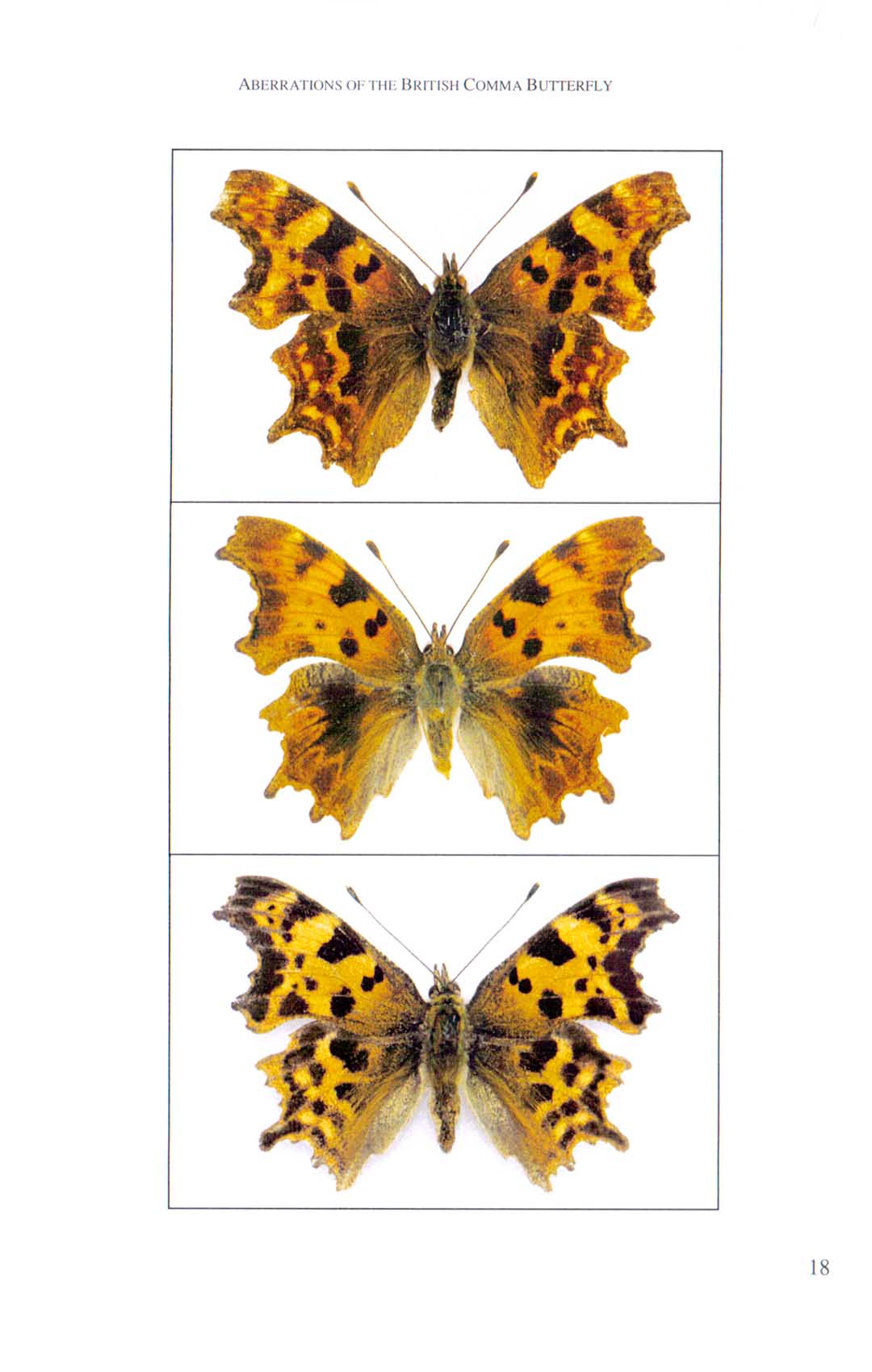

The laudable aim of this series is to cover the aberrations of all of our butterfly species in individual publications. Some groups are less prone to aberration than others; the skippers and hairstreaks for example, and these will be covered collectively. Both books provide very intimate pictures of the early life stages as well as a comprehensive series of excellent quality photographs of both upper and under sides of virtually all the known aberrations.

I say virtually because, in a few cases, only the one individual aberrant butterfly exists or existed and which has proved impossible to track down. It is clear that the author has carried out a very thorough examination of museum specimens and private collections all over the country; some of which are historic whilst others are more recent. I note that some Ringlets were provided by Mr. M.C. White from South Yorkshire.

Some aberrations are very striking: a Comma ab 'castanea' or Ringlet ab 'ochracea' won't escape notice for long. The majority are far more subtle, especially the Ringlet where most of the aberrations involve the spotting (or lack of it) on the underwings, shape and number of spots as well as background colour. There is also a wide variation in the shape of the eponymous Comma, some of which form a complete circle.

Neither book covers genetics or other reasons for aberration; this is amply dealt with in Russwurm and Harmer and there is no need to repeat this information here.

These two books provide the best and most complete series of aberrations that exists in our butterfly literature. It will certainly inspire me to look more closely at the butterflies I see.

The Aberrations of the Orange-tip is the next publication in the pipeline, although the current restrictions have hampered the author's research through lack of access to museums and other collections.

I heartily recommend these two books to anyone with an interest in the aberrations of our butterflies. It certainly promises to be a very informative and exciting series.

Both books Abberations of the Comma and Aberrations of the Ringlet are available to BC members at a reduced rate of £12 each plus p&p, please contact Paul Dunn at: ctmpublications@gmail.com